Hint: it isn’t optimism.

A tale in three parts:

Part I: The Stockdale Paradox

On September 9th, 1965, Admiral Jim Stockdale was flying on a mission over North Vietnam when his aircraft was struck by enemy fire.

He ejected and parachuted into a small village, where he was promptly taken prisoner. Stockdale remained in the infamous Hanoi Hilton for more than seven years.

In his book Good to Great, James Collins describes a conversation he had with Stockdale about how he coped in the POW camp. Who, Collins wanted to know, didn’t make it through?

“Oh, that’s easy,” said Stockdale, “[It was] the optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.”

Seems strange, right? We talk so much about the need for optimism. To have hope. And yet according to Stockdale that’s exactly what we shouldn’t do.

So if optimism is a no-go, what did work? Here’s what Stockdale described as his winning strategy:

“I never lost faith in the end of the story, I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which, in retrospect, I would not trade…

“This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end — which you can never afford to lose — with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.” (Emphasis mine.)

That tension — between the faith that we will prevail and the brutal facts of our current reality — became known as the Stockdale Paradox. It’s what Brené Brown calls “gritty facts and gritty faith.”

And it is exactly what we need right now.

Part II: The brutal facts

Let’s start with the brutal facts of our current reality.

1. Except in countries that have taken extraordinary measures, the pandemic is tracking almost exactly per our worst-case scenario.

In the March 19 Situation Report, the World Health Organization said it took three months to get to the first 100,000 cases, and 12 days to get to the next 100,000.

We’ve since added another 100,000 in three days.

As I wrote two weeks ago, these are exponential curves. They are not easy to get your head around. But they are the reason this is a global emergency. Not because of where we are today, but because of where the trajectory is taking us.

Every country that hasn’t taken extreme measures to stop the spread is on an exponential curve. Here is how long it’s taking each country to double their cases. This chart is on a log scale, which means a straight line is actually an exponential curve. The steepness of the line tells you how quickly it’s doubling.

You can just see Italy starting to slow the rate of growth, thanks to the fact that the entire country went into strict lockdown on Tuesday, 10 March. Other countries, including the US, are speeding up.

Note that the above only references confirmed cases. Because of the lack of testing, the number of true cases is almost certainly many times higher.

Fears that the system will be overwhelmed are being realised in country after country as they start to hit a critical mass. Doctors are having to make triage decisions on who is worth treating. There is a shortage of tests, beds, ventilators, PPE.

(How bad is the PPE shortage? TV shows about hospitals are donating their PPE to actual hospitals.)

2. Everything — and everyone — is affected.

People talk about supporting affected industries. But what industry isn’t affected?

Yes, tourism, airlines and events.

Also: restaurants, cafes, movie theatres, bowling alleys, gyms, advertising, retail, freelancers, education, makeup artists, hair dressers, nail salons, massage therapists, taxi drivers, and anyone who supplies those businesses.

There are industries facing increased demand that aren’t necessarily geared up to respond — essential industries like technology, government, and, of course, healthcare.

Almost every industry is affected.

The policy response encompasses global health, diplomacy, domestic health policy, border and travel controls, foreign aid, economic levers, and more.

But it’s not just industries and policy. It’s people.

I live in Christchurch, New Zealand. Nine years ago, we had a devastating earthquake that killed 185 people and destroyed huge chunks of our city.

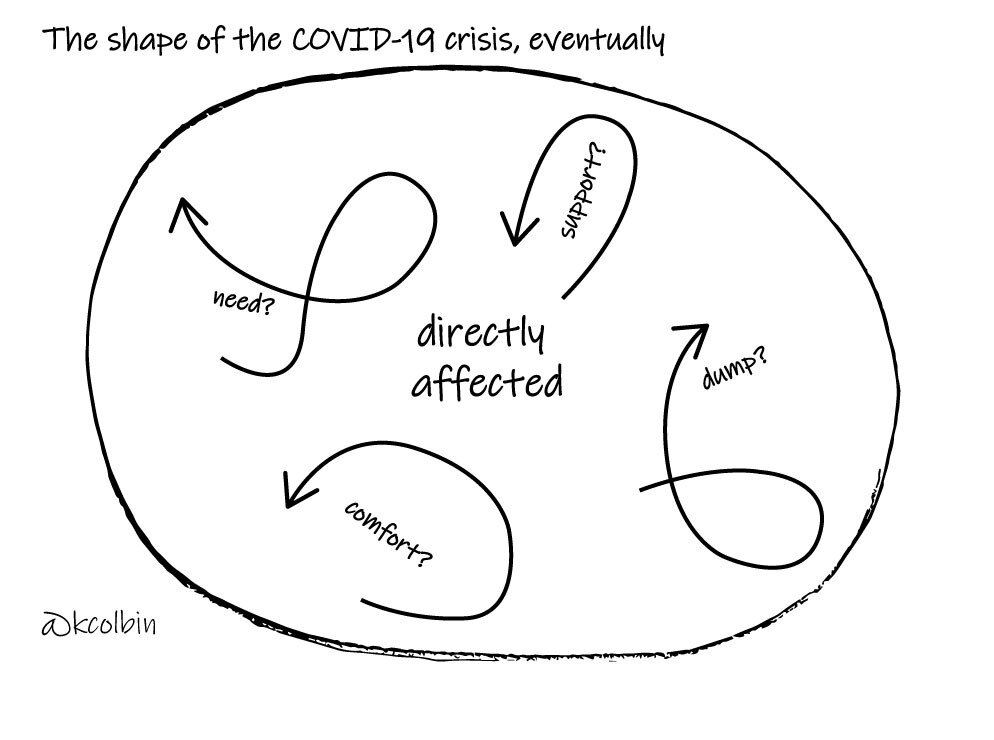

With a disaster like that, people are affected in layers. First, you have the people who were directly affected: the people who were killed, injured etc. Then you have the people who were very affected: first responders, spouses, kids, etc. The people supporting them are somewhat affected, and so on until you get to the folks who weren’t affected at all:

Typically the people in the farther-out circles are in a position to support the people in the closer-in circles — and the way the people in the closer-in circles get through it is by relying on people who are farther out.

Susan Silk and Barry Goldman described a version of this as Ring Theory:

But as the pandemic spreads, it reaches more and more of us, until all we get is this:

Our usual system of relying on each other becomes brittle, because everyone is drained and depleted.

There is no country operating normally that can bail us out. No person with full emotional reserves to be our constant shoulder to cry on. There is only us: fragile, frail, and fraying at the seams, doing what we must to keep ourselves together.

3. As a result of that interconnectivity, the economic impact will almost certainly be bigger than we think.

With the subprime mortgage crisis, a massive problem in one sector of the economy created a domino effect that ultimately disrupted the world.

We are facing a massive problem in most sectors of the economy. And that problem is likely to be sustained over a significant period of time.

Here’s how the current stock market decline compares to the 2008/2009 and 1929 crashes:

Source: https://imgur.com/lnAti4o

Today’s Washington Post features this headline: “U.S. economy deteriorating faster than anticipated as 80 million Americans are forced to stay at home,” adding, “Already, it is clear that the initial economic decline will be sharper and more painful than during the 2008 financial crisis.”

4. We are going to be on this rollercoaster for longer than we think.

After the earthquakes in Christchurch, people kept telling us to buckle in: It’s a marathon, not a sprint!

We tried. We really did. But still, everything took longer than we hoped, and people had to fight their insurance companies and the government for years, and it was all super super hard.

That was an acute trauma — the quakes — followed by a long period of recovery.

With COVID-19, we are just at the beginning of the initial trauma.

We are not re-opening in two weeks.

We should not be planning what we’re going to do “when this is all over.”

The dark cloud we’re heading into is going to be where we live for a while.

Before we think about what we’re going to do when we’re out the other side, we first need to figure out how we’re going to live in the cloud itself.

Part III: The faith that we will prevail

So, yeah. I still don’t think we’ve started to get our heads around how massive this is, for how many of us, for how long.

I still don’t think we’ve started to get our heads around how much all of our lives are now changed, forever.

We are the people they will be writing about in the history books. This is one of those moments that leaves a mark in the geological record: here is where the asteroid hit; here is the COVID-19 pandemic.

But I have faith that we will prevail. And you should, too. Here’s why:

1. We know what we need to do.

We need to buy time.

Tomas Pueyo, whose article “Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now” has been read over 40 million times, came out with a new article yesterday called “Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance.”

In it, he builds on the paper from Imperial College London that looked at the difference between mitigation — where we just try to flatten the curve a bit — and suppression — where we take strict measures to bring the epidemic under control.

Long story short: mitigation isn’t good enough. We need suppression. Suppression allows us to buy ourselves time, if we’re willing to do what is necessary. But we have to act now, and we have to act aggressively.

How did China stop the exponential transmission of the virus? They took extraordinary measures. Check out this first-hand account of someone traveling to China yesterday, which includes these two tweets:

The China model isn’t the only one we might follow. South Korea’s approach is less draconian but also effective: aggressive testing — more than anywhere in the world except Bahrain — combined with extensive efforts to isolate infected people and trace and quarantine their contacts.

And we don’t have to wait for the government to tell us what to do. Every single one of us must be doing our part to #stopthespread.

The actions we need to take might seem difficult. But there are plenty of problems for which we don’t know what we need to do. Here, we have clarity. We just need to act.

2. A vaccine and a cure are both possible and likely, given time.

In order for something to happen, it needs to be physically possible and there has to be sufficient incentive to make it happen.

In an interview with WIRED this week, Larry Brilliant, the epidemiologist who helped eradicate smallpox, said, “By slowing it down or flattening it, we’re not going to decrease the total number of cases, we’re going to postpone many cases, until we get a vaccine — which we will, because there’s nothing in the virology that makes me frightened that we won’t get a vaccine in 12 to 18 months.” Physically possible.

We’re looking at the greatest challenge to the world order in our lifetimes. The cost is already in the trillions. There’s ample incentive.

Already, we’ve fast-tracked a vaccine to human trials. Found some existing drugs, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, that may be effective in treatment.

Gautret et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents — In Press 17 March 2020 — DOI : 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949

These are EARLY DAYS for any potential treatment. Do not let these advances make you complacent or turn you away from the brutal reality of our situation.

But understand that there is a future in which we will have both a vaccine and a cure. We just need time.

3. There are some positive side effects.

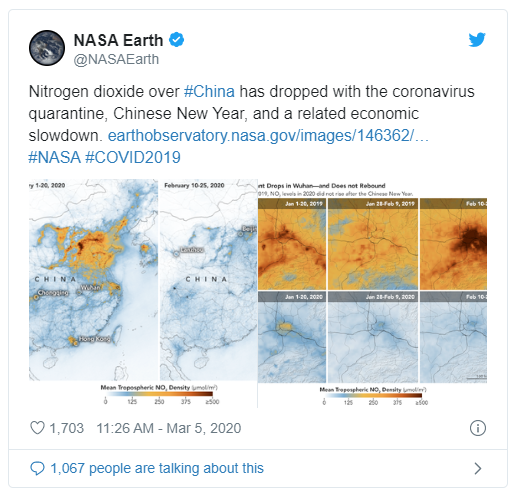

Thanks to the reduced economic activity, air and water quality are improving. Nitrogen dioxide in the air over China and Italy has dropped.

And our animals are pretty happy we’re home.

4. People are amazing.

The world is mobilizing.

In their most recent newsletter, my friends at Future Crunch describe a string of donations:

Tens of thousands of FFP3 masks for Italy’s healthcare workers from the consumer electronics giant Xiaomi

50 tons of equipment for China from the EU, when China needed it, and then

2 million surgical masks, 200,000 N95 masks and 50,000 testing kits for the EU from China, when the EU needed it

600,000 masks to frontline health workers in the Philippines by Manny Pacquiao

1 million masks and 500,000 testing kits to the US by billionaire Jack Ma, on top of 1.8 million masks and 100,000 test kits he’s already sent to Italy and Spain

1 million surgical mask supplies to Japan, Korea, Canada and France by Trip.com

People are working on open-source ventilators. Louis Vuitton has re-purposed their factories to make hand sanitiser. The number one recommendation on the official New Zealand government COVID-19 website is, “Be kind.”

We’re seeing the heroism of our front-line workers: our doctors, nurses, truckers, food suppliers. The other day I was brought to tears by this thread:

People are creative. We’re heartfelt. We’re funny AF.

And we’re philosophical. In the New York Times a couple days ago, Alain de Botton wrote about a book called “The Plague,” by Albert Camus. It’s the story of a fictional virus that kills half the population of an “ordinary town” in Algeria.

De Botton wrote, “For Camus, when it comes to dying, there is no progress in history, there is no escape from our frailty. Being alive always was and will always remain an emergency; it is truly an inescapable ‘underlying condition.’ Plague or no plague, there is always, as it were, the plague, if what we mean by that is a susceptibility to sudden death, an event that can render our lives instantaneously meaningless.

“This is what Camus meant when he talked about the ‘absurdity’ of life. Recognizing this absurdity should lead us not to despair but to a tragicomic redemption, a softening of the heart, a turning away from judgment and moralizing to joy and gratitude.” (Emphasis mine.)

We will get through this, one way or another. But let’s hold fast to the idea that we can get through it with a softening of the heart, a turning away from judgment and moralising and a turning towards joy and gratitude. Let’s hold fast to what Stockdale said: that this shall be the defining event of our lives, which, in retrospect, we would not trade.

We must have the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of our current reality, for that is the only way we will be able to take the necessary measures to address them. But we will prevail in the end. On that we should have no doubt.

As New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said, be strong. Be kind. We will be okay.

Ngā mihi mahana,

Kaila

Kaila Colbin, Certified Dare to Lead™ Facilitator

Co-founder, Boma Global // CEO, Boma NZ

Boma Global is hosting a free, virtual, global conference on COVID-19 on Monday, 23 March, with more than 60 speakers from 20 countries on 6 continents. Learn more and register here.